Randy Babbitt has been in charge at theFederal Aviation Administration for about seven months, but his “to do’’ list filled up quickly. The next year will be crucial for his tenure as the top aviation regulator, and is likely to have a broad impact on air travelers.

Just as he was still settling in, several issues exploded in front of him, like outrage over the experience and actions of a regional airline crew flying on behalf of Continental Airlines after a crash near Buffalo, N.Y., or two pilots working laptop computers instead of paying attention to their Northwest Airlines flight. Some he has set out to tackle himself, like several safety concerns. Some hornets’ nests he inherited, like the slow pace of modernization of the nation’s air-traffic control system, a program dubbed “Next Gen.”

“It’s a huge challenge but it’s a good challenge,’’ Mr. Babbitt said in an interview. “We’re going to do some really interesting things. We’re making strides in air safety.’’

After a news conference in Houston highlighting new air-traffic control technology in use over the Gulf of Mexico, Mr. Babbitt talked about plans for the next year, when the FAA will roll out a slew of changes that will impact air travel. New training standards will likely be proposed for regional airlines, requiring them to step up to training levels practiced at mainline airlines.

“I’ve been a long advocate of one level of safety,’’ he said.

The FAA will also put forward new rules on pilot duty time. Fatigue has become a major concern—pilots can be scheduled for no more than eight hours of actual flying, but they can be on duty as long as 16 hours, and then back at it with a short night’s sleep. A committee of 18 people from across the industry has studied the issue, including the science of sleep and fatigue, and come to consensus on some changes. But they couldn’t agree “on more than a casual few,’’ Mr. Babbitt said. Airlines and pilots don’t see the issue eye to eye, so the FAA will decide.

The FAA has drafted new rules and they are now being finalized, for publication likely by early spring, he said. A transition period will be proposed to give the industry time to adapt – airline schedules will need to be reworked, labor contracts may have to be renegotiated, the economics of the business may change and where pilots will be based may change.

There’s broad support, Mr. Babbitt said, for letting pilots fly at least a little bit more than eight hours a day. A reduction in the length of time they can be on duty also is likely. That means less time spent sitting between flights, for example, and likely more time off duty for rest before getting back in the cockpit the next day.

“We want to make sure we have a fair system that … achieves a new level of safety,’’ he said.

He also thinks the country will begin seeing some successes in the FAA’s modernization effort.

“I’m really optimistic. Next-Gen is going to be sort of `self-invigorating.’ As we begin to show successes, which we are doing here today, and people see this is actually working and begin to see what the potential is, I think the rest will follow,’’ he said. “The problem that we suffered is that there was a lot of time spent on the drawing board. … But now it’s left the drawing board.’’

For travelers, the worry is it will come too late. If new technology doesn’t roll out fast enough as the economy rebounds and traffic returns to the sky, air travel will grind towards gridlock again as it did in 1999 and 2000.

“My true wish is that we can implement the Next-Gen technologies and deploy approaches, procedures and equipment at a faster rate than the traffic can build,’’ he said. “I’d love to think that delays will decrease in time as opposed to increase in time as traffic comes back.’’

Realistic? “I think so.’’

Latest from Aerospace Manufacturing and Design

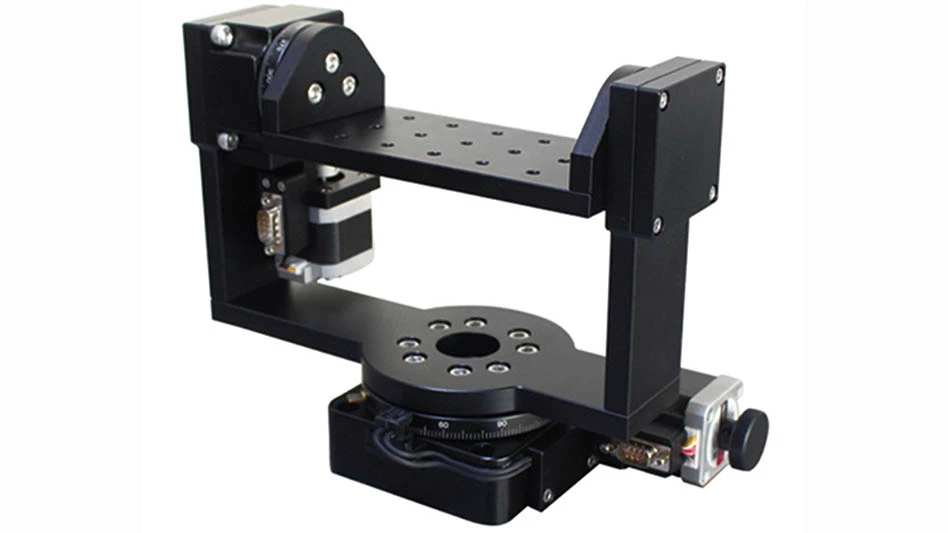

- Precision XY gantry system

- Archer to test Starlink onboard its Midnight air taxis

- System eliminates cage-creep in sliding bearings

- Bodo Möller Chemie signs worldwide supply contract with Airbus

- Sandvik Coromant's CoroTurn Plus turning adapter

- ZOLLER Technology Days & Smart Manufacturing Summit May 13-14, 2026 in Ann Arbor, Michigan

- Walter's TC620 Supreme multi-row thread mill family

- ThermOmegaTech achieves CMMC Level 2 C3PAO certification