PHOTO CREDIT: BIRK MANUFACTURING INC.

Space presents some of the harshest operating conditions for electronic systems. In applications including satellites, space suits, spacecraft and payload systems, flexible heaters are critical components. Despite the environment, these flexible heater assemblies must operate with precision and reliability to enable successful and safe missions.

This article explores the environmental challenges of space – how vacuum conditions, radiation, and electrical interference can compromise performance, and the material and design strategies used to safeguard flexible heaters and their integrated electronics. Specifically, we delve into ultraviolet (UV) shielding, electromagnetic interference (EMI) suppression, system isolation, heat transfer in a vacuum, and circuit redundancy to meet the rigorous demands of space applications.

Heat transfer and extreme temperatures in space

Space is a near vacuum environment – a vast, nearly empty space with very low density and pressure. On Earth, thermal management relies heavily on conduction and convection, processes that require direct contact with matter (solid for conduction, and liquid or gas for convection). But space is devoid of the molecules that facilitate these forms of heat transfer. In practical terms, this makes thermal regulation in space much more complex.

Components in orbit are also exposed to extreme heat on the side directly facing the sun, and extreme cold temperatures on the other, leading to sharp thermal gradients. Heater assemblies must be carefully engineered to accommodate these differences while maintaining stable conditions.

Reducing radiation exposure with UV shielding

Outside Earth’s atmosphere, UV radiation is unfiltered and, therefore, vastly more intense than on Earth. This radiation can affect polymers, adhesives, and electronic components, accelerating the degradation of components and materials, which can lead to premature equipment failure. In satellite systems and other space equipment, UV exposure is a major threat.

To counter this, flexible heaters designed for space applications must include a UV-reflective barrier. The most common material used is aluminized polyimide. This material is essentially a metallized foil that reflects UV radiation, protecting the heater as well as its sensors and electronic components from degradation.

This shielding layer is typically laminated directly onto the heater and encapsulates its complete geometry. However, the material is fragile, requiring meticulous handling during manufacturing. Often, the lamination process occurs in a cleanroom, which helps prevent contamination that could compromise the adhesion or reflectivity of the shield.

Beyond physical protection, UV shielding also contributes to thermal stability. By reflecting solar UV rays, it helps maintain consistent heat profiles across the heater’s surface, even when one side is exposed to intense fluctuations. This is critical in avoiding thermal spikes that could interfere with sensor readings or compromise component alignment.

Mitigating electrical noise with EMI shielding

EMI is also a key concern in space systems, where dense arrays of sensors, communications equipment, and power supplies operate in close proximity. Each component can generate electrical noise that, if not managed, may interfere with signals, distort readings, or degrade overall system performance.

Flexible heaters and their associated electronics are not immune to this issue. While heaters themselves are relatively simple resistive elements, they incorporate sensitive temperature sensors like thermistors or resistance temperature detectors (RTDs). These can be disrupted by EMI, compromising the precision of their thermal control loops.

To protect against this, heater assemblies can include electrically conductive carbonized polyimide layers. These layers serve as EMI shields, redirecting electrical noise away from vulnerable circuits. The shield is typically installed as an independent plane above or below the heater’s active circuitry and is electrically grounded.

In some designs, this shielding extends beyond the heater to include wiring, connectors, and other vulnerable points. When applied consistently, EMI shielding not only protects the heater’s components from ambient noise but also prevents the heater assembly itself from emitting interference that might affect other nearby components.

System isolation protects the larger mission

Anything can happen in space. If an issue or damage occurs in one area, it can threaten the entire system, especially in tightly designed environments such as satellites. Isolation strategies restrict any potential issue to the smallest possible footprint. For heater assemblies, electrical isolation can be achieved in the same way as the EMI shielding. Carbonized polyimide can be incorporated into the heater design as a ground plane.

However, implementing isolation requires close coordination between the heater manufacturer and the system integrator. The integrator must define the necessary precautions and constraints of the design, while the heater manufacturer engineers the right heater and sensor design to support those constraints.

Designing for fail-safe operation with circuit redundancy

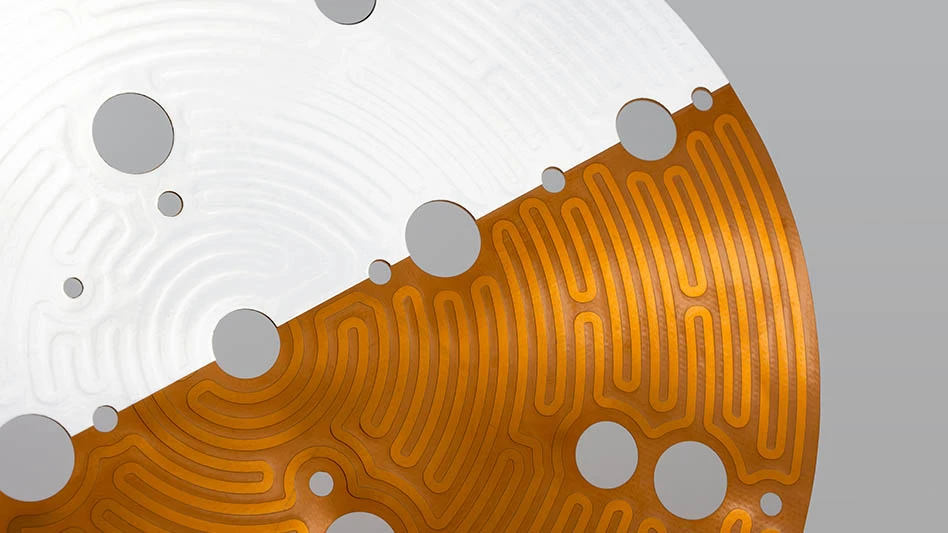

Redundancy is an important insurance policy when designing for space applications. For flexible heaters, this often means embedding multiple circuits into a single assembly. If one circuit fails, a backup can immediately take over, maintaining thermal control without interruption.

However, creating redundant circuits is not as simple as duplicating traces. A heater’s surface area is finite, and any additional circuit must share that space without compromising the thermal properties of the device. Engineers must carefully stagger traces and optimize routing to ensure that both primary and backup circuits provide even heating. This becomes particularly challenging in areas with complex geometries, cutouts, or mounting holes. This complexity requires both knowledge and expertise.

The role of testing in space-ready thermal systems

A final, but critical, factor in ensuring successful space applications is proper testing. Aerospace components must comply with stringent standards, often defined by NASA, the European Space Agency, or other regulatory bodies. These tests can include thermal cycling, vibration, humidity exposure, and so on.

Historically, manufacturers have relied on third-party labs for validation. However, the more advanced companies bring these capabilities in-house, enabling faster iteration and reducing costs. In-house testing also fosters deeper technical understanding, allowing teams to fine-tune designs based on performance data.

Complex engineering for today’s space applications

Designing for space applications requires substantially more engineering expertise than terrestrial applications. Additionally, those designs must be manufactured with incredible precision to achieve a successful product. Each feature discussed in this article is a critical safeguard against the unpredictable and unforgiving conditions of space.

Birk Manufacturing engineers and manufactures flexible heaters, temperature management, and full thermal solutions for space applications. Our innovative and experienced team has a deep understanding of the complexity of designing and manufacturing the highest quality products for mission critical applications.

Birk Manufacturing Inc.

https://birkmfg.com

About the authors: Michael Blair is Engineering Manager, and Scott Phelps is VP, Birk Manufacturing.

Latest from Aerospace Manufacturing and Design

- Dassault Aviation unveils the Falcon 10X

- Industrial round bumpers

- Defense Industry Trends webinar with Greenwich Capital Group

- Air Astana finalizes order for 25 Airbus A320neo family aircraft

- Syensqo showcases high-performance sustainable composites at JEC World 2026

- Multi-axis laser processing system

- Daher accelerates industrialization of thermoplastic composite upcycling

- Orizon Aerostructures deploys Flexxbotics platform