Fitzpatrick Manufacturing Co. is a high-tech job shop, crafting super-precise parts for machines used in everything from robotics to aerospace to oil exploration.

Macomb Community College lies a few miles down the road in this Detroit suburb. Sometimes it's hard to tell where one ends and the other begins.

Fitzpatrick's 93 employees are constantly in and out of Macomb, taking classes with a tuition reimbursement from the company. And so frequently are Macomb instructors at Fitzpatrick's plant to offer lessons that the company built a classroom.

Company President Kevin LaComb describes the school as concierge-style job training.

"You tell them what you need, pretty much in a couple days, they have an instructor," he said. "Other people say, 'This is what we're offering, but we can't deviate from what we do.' Macomb customizes just what we need."

Community colleges, long the under-loved stepchildren of American higher education, still don't get the dollars of their four-year counterparts, but they're standing very much in the spotlight these days. President Barack Obama made them the focus recently when he unveiled his proposed budget.

Why all the attention? One reason is that so-called "middle-skill" jobs look like the most promising way to rev up an economic recovery. Even when unemployment was more than 10% nationally last year, a survey conducted by the Manufacturing Institute found that two-thirds of manufacturing companies reported moderate-to-severe shortages of qualified workers to hire.

That kind of training is the sweet spot for the country's 1,167 community colleges.

Community colleges also can be speedy and agile. Most teachers aren't tenured professors but professionals plucked from changing fields. The schools can move in weeks or sometimes days, earning a reputation as the only corner of higher education that operates at private-sector speeds.

In Michigan, where unemployment peaked at 14.1% in 2009 but has since fallen to 9.3%, leaders hope that agility will accelerate a manufacturing rebound. One program offers free training for companies filling new jobs. In return, state income taxes generated by the new positions kick back to the school for two years, and then to the state. Organizers of the program said it has supported 8,000 new jobs.

Many Michigan students moving through such programs used to work at companies most Americans have heard of: Electrolux, Alcoa, Whirlpool, and the Big Three automakers and companies that supported them. The companies where they're now training for jobs are younger, smaller and need tightly tailored training.

"For small- and mid-size employers who actually generate a lot of the jobs in this economy, developing that kind of training for five or 10 employees that they're going to hire, it's not economically feasible," said Rachel Unruh, associate director of the National Skills Coalition.

That's where community colleges come in.

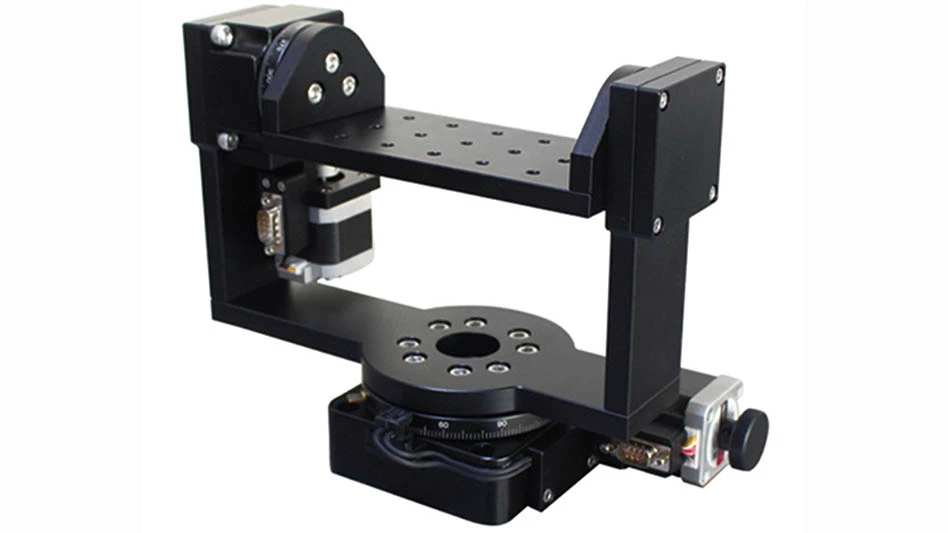

At Fitzpatrick Manufacturing, $100,000 machines do work that used to be cranked by hand — but somebody has to know how to run the machines. For some parts, the margin of error can be no more than .0004 inches.

One typical "middle skill" is called "geometric dimensioning and tolerancing," or GDT. It's a language of symbols used in engineering blueprints. On two recent Saturdays, Macomb instructors came by to help employees brush up on GDT.

"To learn calculus that you would learn in an engineering curriculum is all well and good," said the company's Mike Fitzpatrick. "But it has nothing to do with us."

In his budget, Obama asked Congress to create an $8 billion fund to help community colleges train up to 2 million workers for jobs in high-growth fields, and to award financial incentives to make sure trainees find permanent work. There were few other details about how the proposal might work, and it faces long odds in Congress.

Latest from Aerospace Manufacturing and Design

- Archer to test Starlink onboard its Midnight air taxis

- System eliminates cage-creep in sliding bearings

- Bodo Möller Chemie signs worldwide supply contract with Airbus

- Sandvik Coromant's CoroTurn Plus turning adapter

- ZOLLER Technology Days & Smart Manufacturing Summit May 13-14, 2026 in Ann Arbor, Michigan

- Walter's TC620 Supreme multi-row thread mill family

- ThermOmegaTech achieves CMMC Level 2 C3PAO certification

- One-touch precision flex locators