This is not an advertising agency’s slogan, it’s something that Prof. Dr.-Ing. Gunther Reinhart of Munich Technical University proves every day: as the Director of the Institute for Machine Tools and Industrial Management (iwb) brings real machine tools into the virtual world of simulation, algorithms and neural networks.

“The machine tool is a particularly ideal choice for practising cognitive issues”, explains Professor Reinhart. “Nowadays, you see, it runs highly complex operations.” These involve firstly technology integration (e.g. laser machining and grinding in a single machine), which can be mastered and operated by staff only with the aid of computers, and secondly automatic handling opera-tions that are susceptible to malfunctions and errors. Sensor networks can act as a preventive here, and computer programs (known as algorithms) can help in the event of malfunctions.

Artificial intelligence, sensor networks and algorithms: no doubt about it, the world of machine tools is turning virtual. For this purpose, research is ongoing within the framework of CoTeSys (Cognition for Technical Systems), an excel-lence cluster for developing cognitive technical systems, subsidised by the German Research Association. CoTeSys’s remit includes incorporating artificial intelligence and fuzzy logic into the production machines. “We aim to use the tripartite requirement of “detect, deduce, deliver” to make machines more proactively autonomous than they used to be”, says Reinhart. Nowadays, production lines are programmed to take some decisions; a network of sensors is now tasked with enabling the machines to obtain information about itself and its surroundings, so as to formulate possible solutions autonomously with the aid of knowledge databases, and translate them into appropriate action. To quote Reinhart: “For each solutional approach, we check whether it is able to meet the tripartite requirement:” “detect, deduce, deliver.” This is not mere ivory-tower research: the “Cognitive Machine Shop (CogMaSh)” subproject has in Munich already created the first cognitive factory that thinks for itself – further facilities are under construction.

Internet of things: when workpieces can communicate ...

One aspect of CogMaSh is the “internet of things”: for this purpose, workpieces are fitted with radio labels, known as RFID tags. For example, a component asks Machine Tool Number Two: “Can you drill a diameter of 50 millimetres on time, or shall I take myself to another machine?” The machine tool says “Yes”, the workpiece concerned uses RFID to book itself a “factory taxi”, and says to the driverless transport system: “Please take me to Machine Number Two.” After drilling has been completed, the workpiece stores information on its status, and the machining quality on its RFID tag.

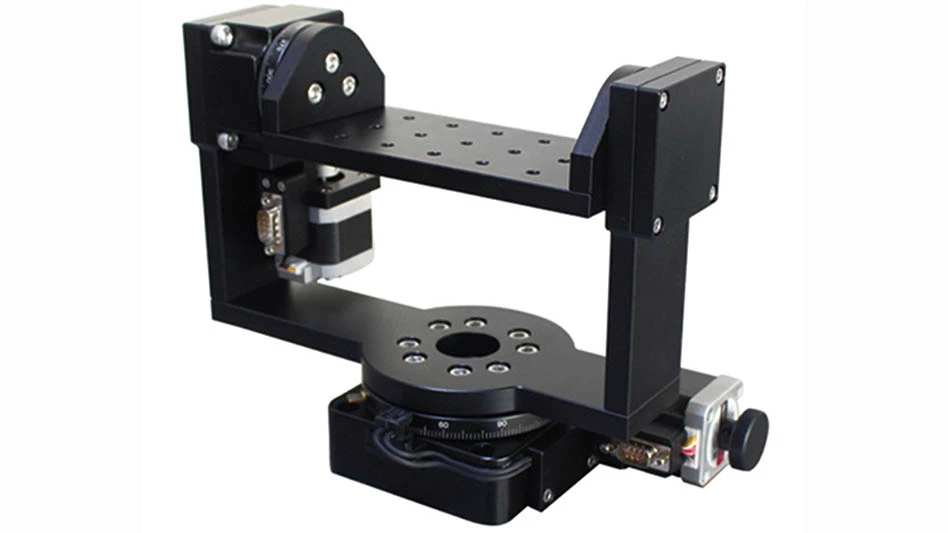

The researchers at the iwb in Munich are also investigating the possibilities of virtual commissioning: they have succeeded in imaging a machine’s physical characteristics, like density, centre of gravity, static and sliding friction coeffi-cients, thus eliminating a defect of a CAD system’s previous geometric data, not based on the fundamental laws of physics. “You then see a components hovering after a gripper has released it, although actually it ought to fall to the ground”, explains the institute’s Director Reinhart. “We’re now incorporating proper physics into the systems.”

Simulation: realtime is crucial

Complex situations are also programmed into the EDP system: these, says Reinhart, also include the simulation of sophisticated machining centres with several control systems, which communicate with each other via a data bus. A manufacturer could use the simulation capability to virtually commission all of a factory’s production lines, test the software and the interaction of the machines, and simulate the reaction to artificially induced malfunctions. The difficult task involved here is primarily performing the simulation in realtime.

To ensure that development work keeps closely in touch with practical consid-erations, the scientist and his team work fruitfully together with the VDW (German Machine Tool Builders’ Association) and member companies like Deckel Maho Pfronten GmbH, Gebr. Heller Maschinenfabrik GmbH in Nürtin-gen and Liebherr-Verzahntechnik GmbH in Kempten. The scientists adopt a twin-track approach to the search for new ideas. “We get a lot of useful input from the internet with its specialised forums and virtual trade fairs like the VDW’s CNC Arena”, reports the expert on virtual reality. “But we also send our scientists to the EMO Hannover so that they can get on-the-spot answers to their questions from machine tool manufacturers and users.”

The challenge: documents from disparate disciplines under one virtual roof

The first practical test for virtual commissioning, however, came not in the field of metalworking, but in beverage bottling. “This involved virtual commissioning of a multi-control-system model”, says Reinhart. “The complexity of this line can easily be transferred to machine tools as well.”

At the moment, however, the machine tool manufacturers are more interested in how documents created in different specialised disciplines can be brought together. So the task involved is to unite CAD depictions of machinery con-struction, electrical schematics, flow charts and programs from the software department under one virtual roof. “With a virtual model, it would then be possible, for instance, to create software automatically using the logic from electrical schematics”, says iwb Director Reinhart with a view to the future.

The research people in Munich, however, simulate not only the technical side of a factory, but the financial considerations as well. They have created a model, for instance, that assesses the risks for the entrepreneur involved. The iwb trialled the system for an automotive component supplier, who was faced with a decision on whether to build a plant in Czechia or Bulgaria. “We calcu-lated the possible spreads for the capital values of these investment projects”, explains Reinhart. “This covered the logistics chain, the dependability of supply, and, of course, developments in wages, which under certain circumstances may soar by up to 500 per cent. You soon realise that in the long term an investment abroad is not always going to pay off.”

Latest from Aerospace Manufacturing and Design

- Archer to test Starlink onboard its Midnight air taxis

- System eliminates cage-creep in sliding bearings

- Bodo Möller Chemie signs worldwide supply contract with Airbus

- Sandvik Coromant's CoroTurn Plus turning adapter

- ZOLLER Technology Days & Smart Manufacturing Summit May 13-14, 2026 in Ann Arbor, Michigan

- Walter's TC620 Supreme multi-row thread mill family

- ThermOmegaTech achieves CMMC Level 2 C3PAO certification

- One-touch precision flex locators