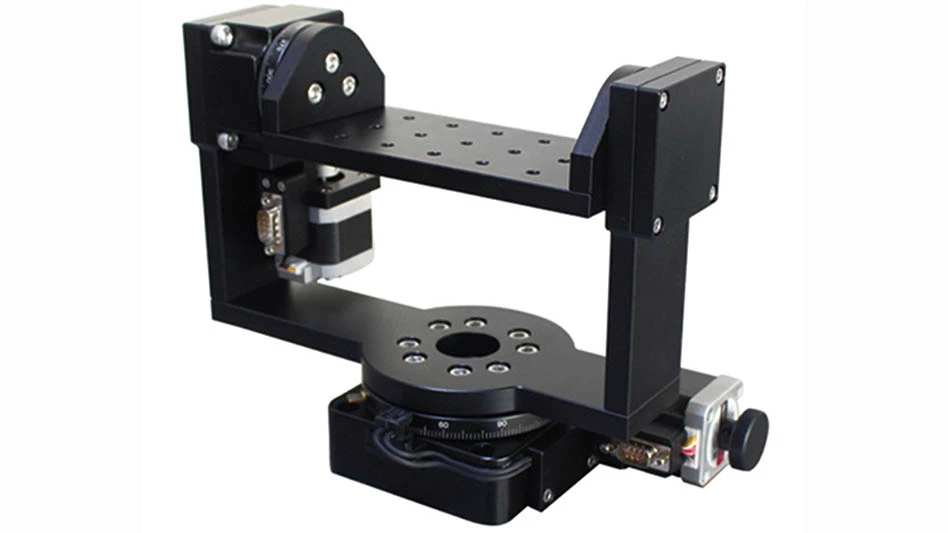

A model undergoes wind tunnel testing at the University of Washington Aeronautical Laboratory.Getting the most return on investment is a business principle that is normally on the minds of business leaders. Given the current economic climate, this principle is more important now than perhaps it has ever been, particularly in the aerospace industry. The magnitude of the cost to develop, and eventually certify, a new airplane can be quite daunting. Experimental class airplanes, not being obligated to meet all of the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) certification requirements, start in the millions of dollars and costs can end up in the tens of billion-dollar range for a transport category airplane. One underlying principle, common in all successful programs, is the early identification of design deficiencies with mitigation resulting in a superior product and a better bottom line.

A model undergoes wind tunnel testing at the University of Washington Aeronautical Laboratory.Getting the most return on investment is a business principle that is normally on the minds of business leaders. Given the current economic climate, this principle is more important now than perhaps it has ever been, particularly in the aerospace industry. The magnitude of the cost to develop, and eventually certify, a new airplane can be quite daunting. Experimental class airplanes, not being obligated to meet all of the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) certification requirements, start in the millions of dollars and costs can end up in the tens of billion-dollar range for a transport category airplane. One underlying principle, common in all successful programs, is the early identification of design deficiencies with mitigation resulting in a superior product and a better bottom line.

Carried out in a wind tunnel, early identification of design deficiencies is often the first validation and verification for a new airplane. The data gathered in the wind tunnel enables designers to determine how many required changes there are, along with the opportunity to make the appropriate changes. It is important to understand that there typically are problems, but the key is to address them in a timely manner. That is what wind tunnel testing is for, delivering the vital feedback to the designers which, in turn, gives them the opportunity to improve the performance and handling of their aircraft.

Consistently working on ways to improve wind tunnel models is always a part of the product development process. Regularly evaluating the design and construction process enables identification of the areas where improvements would be beneficial. The wind tunnel model determines how productive a wind tunnel test can be. How fast the model can change from one configuration to another is very important and includes not only how long it takes to change the control surface deflections, but also how fast the wings, flaps, and tail surfaces can be added or removed to get the desired configuration of interest. Accounting for all of this when designing the model determines how quickly changes can be made – all being vital for process improvements.

While as much model design standardization as possible is desired, within the limitations imposed by a given vehicle configuration, having an institutionalized manufacturing process that is too rigid can stifle innovation. However, in an effort to keep the model as simple as possible, a guiding principle of model design is having low part count with ease of manufacturing. As an example, an additional refinement in model design is the minimization of the number of external fasteners on the vehicles critical surfaces. Holes for fasteners on the lower pressure surface of wings and the tail often require constant attention during testing. Covering or filling each hole, to provide the model with a smooth outer mold line is a must so alternatively, any hole not placed in those critical surfaces will reduce the number of issues related to configuration repeatability.

Material costs are typically a small fraction of the total model cost, but the material’s machining properties are often a more important factor in the overall cost. Machine time and labor are by far the largest portions of a model’s cost, so every effort is made to incorporate industry manufacturing best practices to lower model construction times and costs.

Each year Aeronautical Testing Services Inc. (ATS), while supporting the University of Washington’s airplane design course, tests and develops innovations in model design, construction and construction materials. Models built for these projects are at no cost, or a reduced cost, and result in wind tunnel models designed and built in a period of three to four weeks, with lessons learned during these models incorporated in other follow-up projects.

One recent design improvement incorporated into follow-up projects are small electro-mechanical motors for remotely-actuated control surfaces. The actuators are inexpensive, strong and robust, and lend themselves quite easily for implementation in wind tunnel models. Additional changes in design practices allow measurement of the resultant aerodynamic loads on the control surfaces in parallel with having those same surfaces powered. The capability to measure hinge moments offers a better understanding of the aerodynamic forces that the model experiences as well as providing some valuable information for the design of the vehicle’s control system.

It is the inclusion of novel features, such as these, that are allowing customers to get more from their testing experience.

Aeronautical Testing Service Inc.

Arlington, WA

aerotestsvc.com

Explore the January February 2010 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Aerospace Manufacturing and Design

- The Lee Company opens Innovation Center

- Precision XY gantry system

- Archer to test Starlink onboard its Midnight air taxis

- System eliminates cage-creep in sliding bearings

- Bodo Möller Chemie signs worldwide supply contract with Airbus

- Sandvik Coromant's CoroTurn Plus turning adapter

- ZOLLER Technology Days & Smart Manufacturing Summit May 13-14, 2026 in Ann Arbor, Michigan

- Walter's TC620 Supreme multi-row thread mill family